The Odds of a Stress-free Vacation

Published: 25th October 2025

Category: Consumer Behaviour

"Never underestimate the probability of being wrong about probabilities." -- Anonymous

An ill-planned trip to Goa turned out to be an eye opener in understanding probability and statistics; topics I had conveniently opted out of during my pre-degree (That’s Class XI and XII for generations born 90s onwards).

It began, as most small adventures do, with a plan and a prayer. A sudden idea: Let’s go to Goa.

Last minute decision, approvals from work and indecision about hotels delayed the train booking.

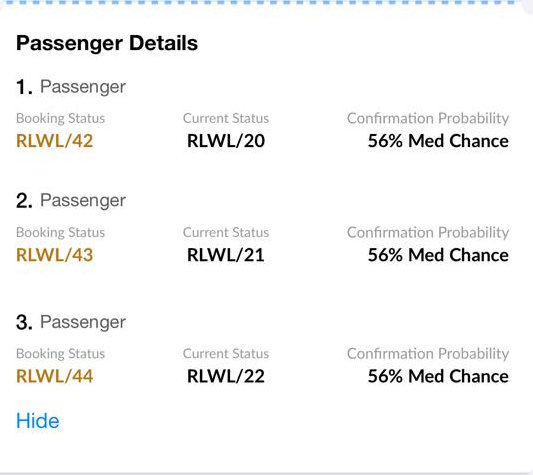

I remember opening the IRCTC (Indian Railway Catering and Tourism Corporation ) site that night, fingers crossed during booking. The screen blinked: WL 42, 43, 44. Not very promising but enough to keep hope alive.

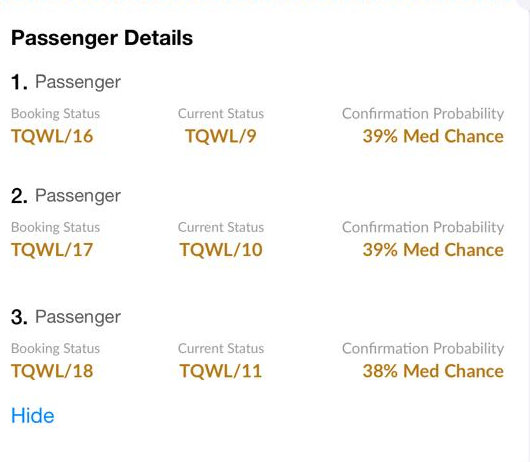

A few days later, I made a second attempt at the Tatkal quota. TQWL 16, 17, 18. All three of us were sweating bullets during the 24 hours before the journey as the tickets were crucial. Money was already paid for stay, tour and return tickets and all of it was non refundable. This was turning out to be a really “stress-free” vacation On the day of the journey, Tatkal booking moved to 3, 4, 5, with 39%, 39% and 38% chance of confirmation. Something in the back of my mind gnawed at the that 1% lower chance.

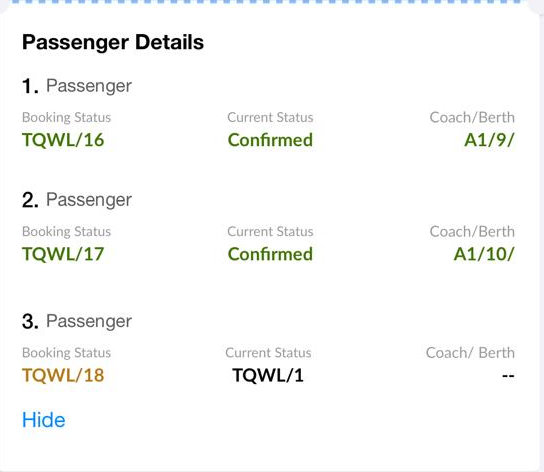

Hours passed. The regular waitlist also moved. 20, 21, 22, with a 56% chance of confirmation. Despite not being fond of maths, I consider myself a man of science and logic. Mathematically, the odds were higher in the general booking as compared to Tatkal booking. Also, as per rules general waitlist is given preference over tatkal waitlist. The first passenger blamed IRCTC, internet connection and the government at our plight, The second called out to all the gods possible, supremely confident that god will ensure that we get the tickets. A firm believer of “Kasht karne se hi Radhika milti hain”, I scrambled around calling friends and agents desperately to get us out on the train. And then came the final chart. Two confirmed seats out of the Tatkal Quota: A1/9 and A1/10. One name remained:TQWL/1. No prizes for guessing who got left out! I fell just one step outside the circle of grace and ended up paying 6 times the price to reach Goa by flight. The others went by train.

While my brain said: The system ran out of space. My mind, jealous and outraged whispered: No, this was selection. They were chosen, I was not.

But lets stick to logic. Probability is the mathematics of chance. It’s the likelihood of the occurrence of an event between 0 and 1, or 0% to 100%. If you flip a coin: P(Heads)=0.5 Half the time, it’s heads; half, it’s tails. Simple, elegant, and measurable. The same mathematics powers modern systems, from stock markets to train booking algorithms. Every number, every “confirmation chance” the railway app shows you, is born from statistics: a collection of historical data, patterns of cancellations, and quota adjustments. Three primary types of probability guide this science:

- Classical Probability : based on equally likely outcomes (like rolling a fair die).

- Empirical Probability: drawn from real data and experience (like how often a waitlist clears).

- Subjective Probability: based on belief, intuition, or personal judgment.

But the events of the trip felt weird.

A 39% chance succeeded. A 56% chance fell short. Tatkal waitlist got tickets, general waitlist did not. Two got seats; one didn’t. A 17 % higher probability did not make a difference to the outcome but a 1 % difference did. This shows the sheer randomness and variance possibility in real life outcomes.

Mathematically, nothing miraculous occurred. Even a 39% probability can happen; that’s how randomness works. But humans don’t live in mathematical space; we live in emotional space.

To my co-passengers, a 39% success felt like divine grace. To my heart, a WL/1 rejection felt like fate. Numbers become irrelevant when they start speaking in human terms.

Here’s the kicker:

The more we learn about probability, the more we realize how little we truly control. Even perfect data cannot predict a single future event with certainty. Each outcome, no matter how calculated, still carries a shadow, the unmeasurable, the unaccounted, the unknowable. Philosophy calls it fate. Faith calls it divine will. All of them point to the same space; the one beyond reason.

We have built a civilization on the worship of logic. We can model rainfall, predict markets, even simulate the behavior of galaxies. And yet, a small line of text on a train ticket: TQWL/1 Not Confirmed, can humble the entire machinery of reason.

Probability is simply a human attempt to tame or model the unknown but does nothing to control it. It gives structure to our thinking and not certainty over outcomes. Statistics gives explanation to past patterns but no certainty over future.

In simple mathematical language, the following is where our theory falls short:

- Probability of an event X = No of favourable outcomes (X) / Total no of outcomes (A)

But the world never reveals all possible outcomes. The denominator 𝐴 is always incomplete. We can never truly know how many possibilities exist; only how many we’ve seen. That missing denominator is where luck lives.

I will illustrate the flaw in application of the theory using the draw of cards example:

- P (a draw is a queen of hearts ) = Number of queen of hearts / Total Cards

But in a real game, the queen may appear in the second draw or the game might end before all 52 cards are drawn. In that case, the probability of drawing the queen conditional on the actual sequence of events could be very different, if only two cards were drawn before the game ended.

This shows that the theoretical formula assumes a complete and known set of possibilities, which life rarely provides. (For purists of theory who may harp on conditional probability, the ratio moves from 1/52 (1.92%) to 2/52 (3.85%).

When waitlisted passengers with a 39% chance confirm while the same on a 56% does not, logic just bows. It acknowledges that the map of knowledge has edges, and beyond those edges lies something unmeasured. Call it coincidence, karma, divine bias, or cosmic symmetry; every name is a metaphor for the same truth: The unknown is greater than the known.

The experience made me realize something profound: We build our models to make sense of uncertainty, but uncertainty is not an error. It is design embedded in life. It’s what keeps the world unpredictable and alive.

Science gives us probabilities but real life unfolds in possibilities and the gap between the two is bridged by sheer luck.